Count Zborowski, Bligh Brothers, Aston Martin, Chitty Bang Bang & the Land Speed Record

I’ve always known that my ancestors were coach builders. Coachbuilding is the skill of designing and manufacturing carriages, and it has been to some extent ever-present in my life. Examples of the ornate, hand-painted coats-of-arms which once adorned the vehicles they built have hung on the walls of our family home ever since I can remember.

These craftspeople - the Bligh side of my family - have been technically inclined for many generations. My mother’s research into our family history in the last few years unearthed a whole host of information about our sprawling family tree, much of it would otherwise have been lost in the sands of time.

This particular story is about the early development of racing cars; the rise and fall industries, companies and individuals. It spans centuries; from my four times great-grandfather William Bligh at the time of the Napoleonic wars, through five generations of my family.

What I discovered through our research are some close family ties to key events in early motorsport, the setting of world land speed records, and the inception of some of the most well known motor vehicles ever constructed. These were already subjects I had independently developed an interest in, and given what I have discovered about this part of my ancestry, perhaps my intrigue was inevitable...

# Louis Zborowski: A white knight

At the heart of the story is a figure whose wealth and passion for speed transformed the fate of two businesses. In the immediate aftermath of the First World War, this youth rescued two businesses from bankruptcy; the first was an early race car manufacturer called Aston Martin, and the other was a coach building firm called Bligh Brothers of Canterbury, our family’s business.

Photo: "Count" Louis Zborowski, centre. Canterbury Historical and Archeological Society

Louis Zborowski inherited his immense wealth aged only 16 years old. It comprised “£16 million ... and 7 acres of Manhattan”. The son of an heiress to the Astor fortune, the teenager had also acquired a taste for motor racing from his father.

His father - Eliott Zborowski - had been a keen amateur racing driver. He is credited with the creation of British racing green and establishing the convention where countries compete under distinct national colours. Yet when Louis was just 6 years old, Eliott was killed participating in the La Turbie hill climb in the mountains above Monte Carlo, Monaco.

After his father’s tragic death in 1903, Louis’ mother purchased Higham Park, a grand house and estate near Canterbury, England. When she died in 1911, the property came into Louis' possession along with the family wealth, and a substantial annual allowance for the teenager.

Despite his youth, Louis Zborowski’s taste for speed quickly developed and he spent much time behind the wheel of fast cars. He accumulated at least eight convictions for motoring offences (speeding, dangerous driving, driving with a suspended licence) before the end of 1915 when he turned 20 years old.

# Bamford & Martin: constructors of racing cars

Zborowski's interests extended to supporting nascent enterprises. Among them was a fledgling race car manufacturer that would become a household name: Bamford & Martin, later known as Aston Martin.

It had been established two years earlier in 1913. Robert Bamford and Lionel Martin began as motor car dealers in London. They built vehicles to compete in racing and hillclimbs, and a number of years later found customers to sell them to.

Seven years on and Robert Bamford departed the business. Freshly rebranded as "Aston Martin", the firm urgently needed a new source of funds to carry on. Lionel Martin decided to sell a slice of it to raise capital.

The buyer was the young "Count" Zborowski. He paid £10,270 for the shares, Aston Martin was saved and with an additional personal contribution by Martin, the business was once again liquid enough to continue.

(For clarity, both Louis and his father seem to have used the title "Count" at times and it's widely noted across a range of historical documents, although there is scant evidence to suggest either legitimately held the title.)

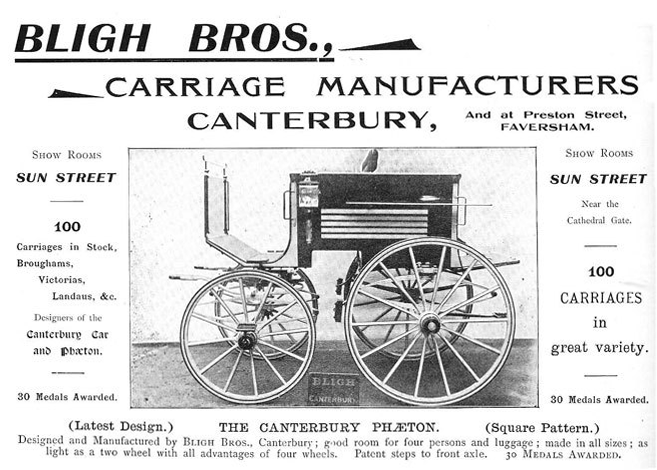

# Bligh Brothers: coach builders

As Zborowski's passion for racing cars started to edge into manufacturing, another story was being written closer to home. This brings us to Bligh Brothers of Canterbury, a firm on the brink of collapse, yet destined for revival under Zborowski's patronage.

Bligh Brothers was around a century old at this point, having been founded just after the Napoleonic Wars by my four times great-grandfather, William Bligh, a wheelwright in Kent 2.

The coach-building and carriage works had been expanded by five of William's sons, and then inherited by three of his grandsons. By the 1870s, they were employing 43 men and 11 boys, and internationally recognised for building high-quality horse drawn carriages and coaches.

The traditional coach building industry started to rapidly transform in the early part of the twentieth century, when motor cars began to compete for the work of traditional horse-drawn vehicles. This change was accelerating in 1913, and just as Bamford & Martin were starting out, newspaper records from that summer show Bligh Brothers had filed a petition for bankruptcy, making attempts to save their ailing business.

Photo: Bligh Bros. advertisment. Credit: Steph's Family History

With the outbreak of First World War the following year, the Bligh’s business was requisitioned to make wheels for artillery cannons, and this improved the condition of the firm for a while. However, by the time peace returned to Europe in 1918 the number of horses which had perished ran into the millions, and any unfortunate animals that remained in France were destined for the slaughterhouse.

At this point, traditional coach building experienced a rapid and catastrophic collapse.

The troops started to return home, and it was in this bleak post-war context that Bligh Brothers seem to have been fortunate to find a renewed purpose — in the position of supplying the youthful Zborowski coachwork for his emerging passion — establishing a stable of early, fast and beautiful motor vehicles.

As it turned out, this included the very earliest of Aston Martin race cars.

It was around this time Zborowski took a stake in the struggling coach-building firm 1.

Like with his rescue of Aston Martin, Zborowski’s timely intervention in Bligh Brothers saved their business. He retained their team to use as his personal staff of coach builders, and invested in their workshops in Canterbury; conveniently located near the estate at Higham Park. By 1921 the leases of Bligh Brothers buildings in Canterbury were held in Zborowski’s name 3.

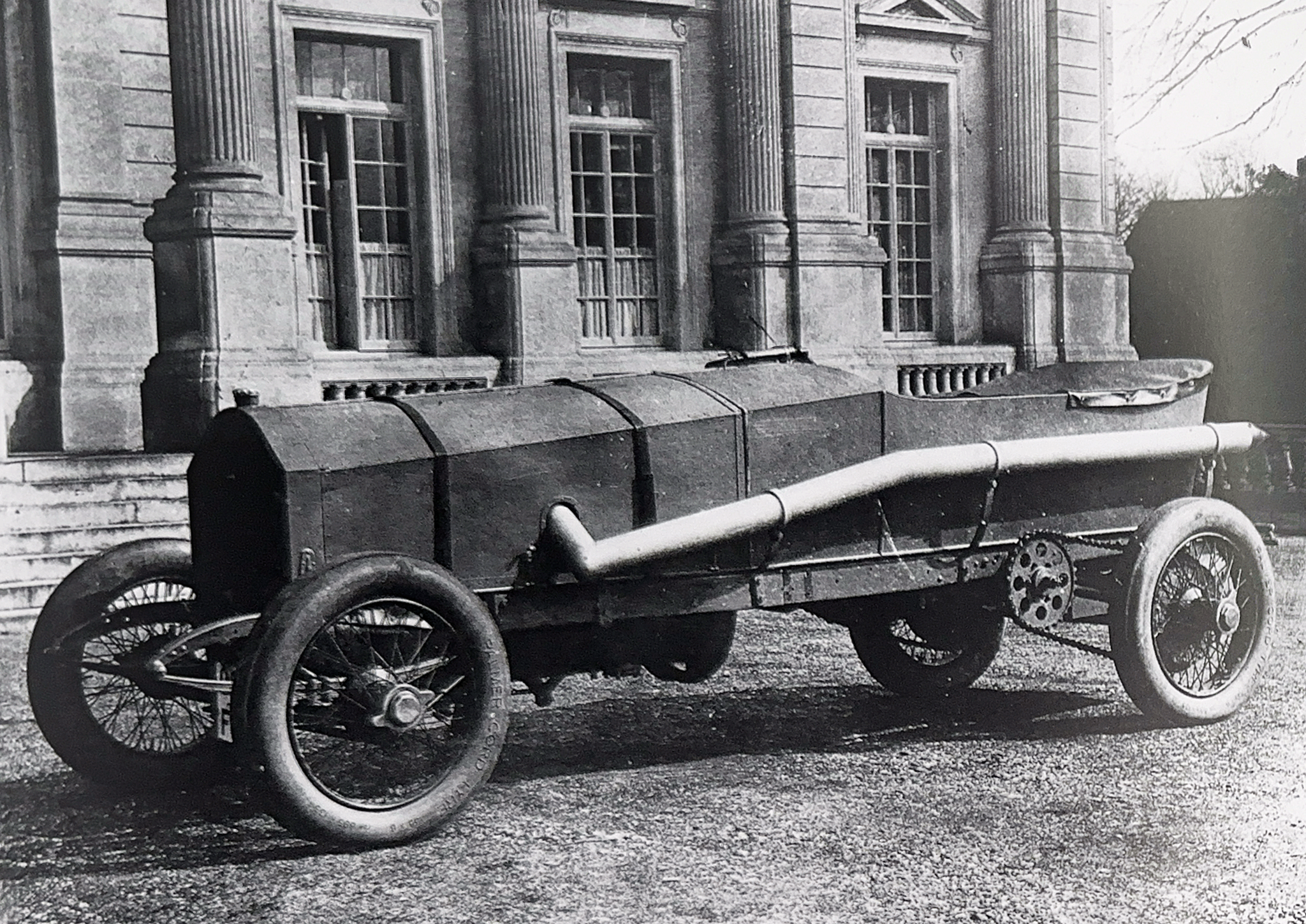

# Birth of a legend: the Chitty Bang Bang cars

The collaboration between Zborowski and the Bligh Brothers set the stage for a new venture. Together, they embarked on creating something that would become legendary, vehicles that would fuel the imagination of generations to come.

At the time, motor cars destined for the aristocracy were not always sold “fully assembled” — with the chassis and coach (body) work often specified independently of each other — and so Bligh Brothers were tasked with creating custom coachwork.

With the help of his school friend and former Royal Flying Corps engineer Clive Gallop, Zborowski started constructing a series of monumental cars inside Bligh Brothers’ workshops.

The vehicles were christened “Chitty Bang Bang", and through a remarkable twist of literary fate these cars were introduced to a worldwide audience. Their fame has endured now for over a century.

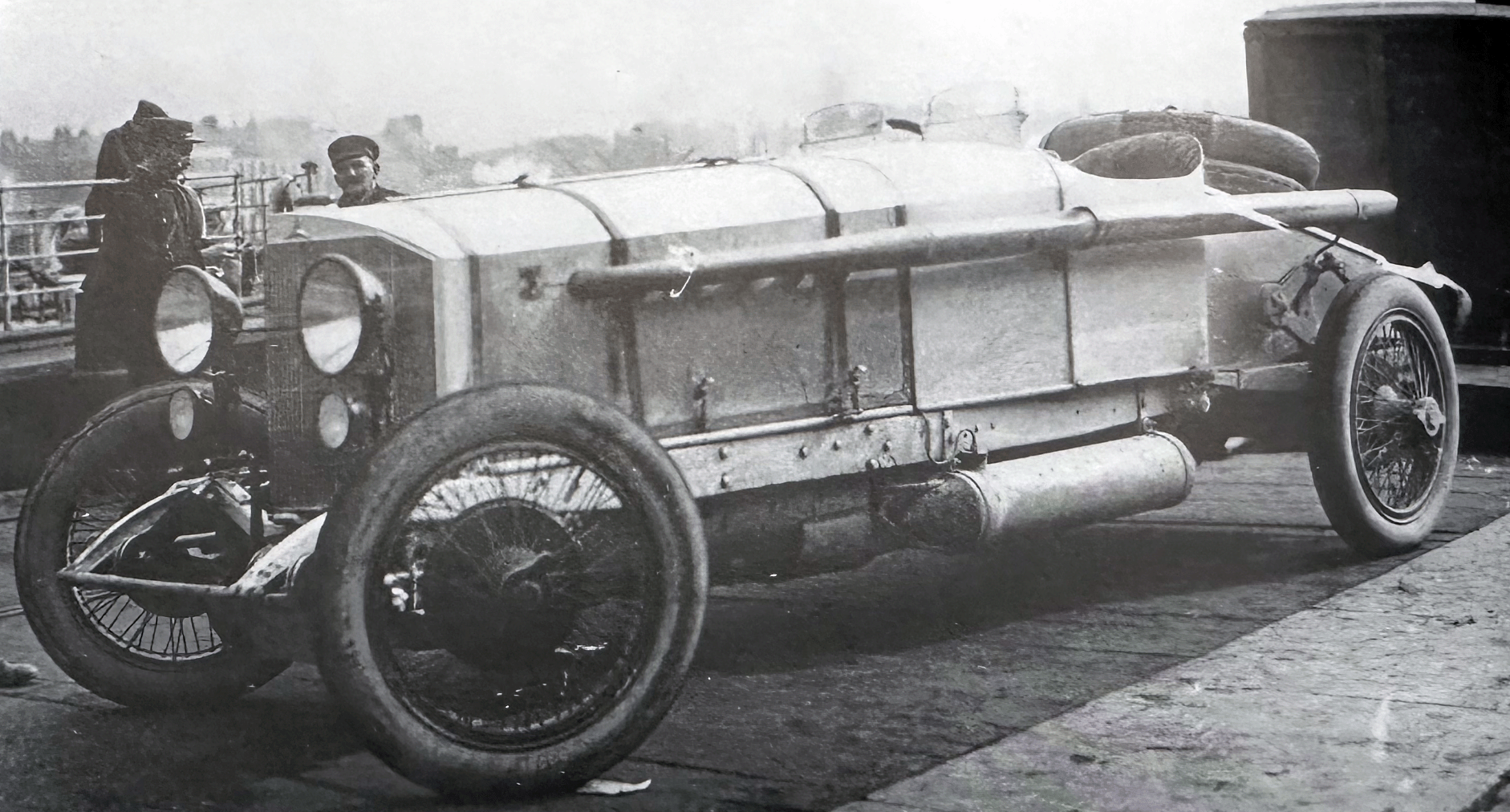

Photo: The enormous first Chitty Bang Bang, in its original 4-seat configuration outside Zborowski's house at Higham Park

The team that Zborowski built — the Bligh coach builders, Len Martin (no relation to Lionel Martin) and Clive Gallop amongst them — provided the mechanical and technical expertise to create these unique vehicles.

The Chitty cars were characterised by comically large aircraft engines.

The largest had a capacity of 23 litres, which dwarfs the engines of even the most extreme modern performance cars.

Louis was a practical man, and liked to roll his sleeves up in his workshops. Those who worked for him recalled he would spend his time whistling away at the lathes preparing components for his cars.

The vehicles were driven between races on Bligh Brothers trade plates. These outings were much to the consternation of the residents of Canterbury who complained about the horrendous engine noise reverberating inside the ancient city walls. The mammoth Maybach engines had been salvaged from the War Disposals Board, having originally seen service as the power-units of German Zeppelin airships.

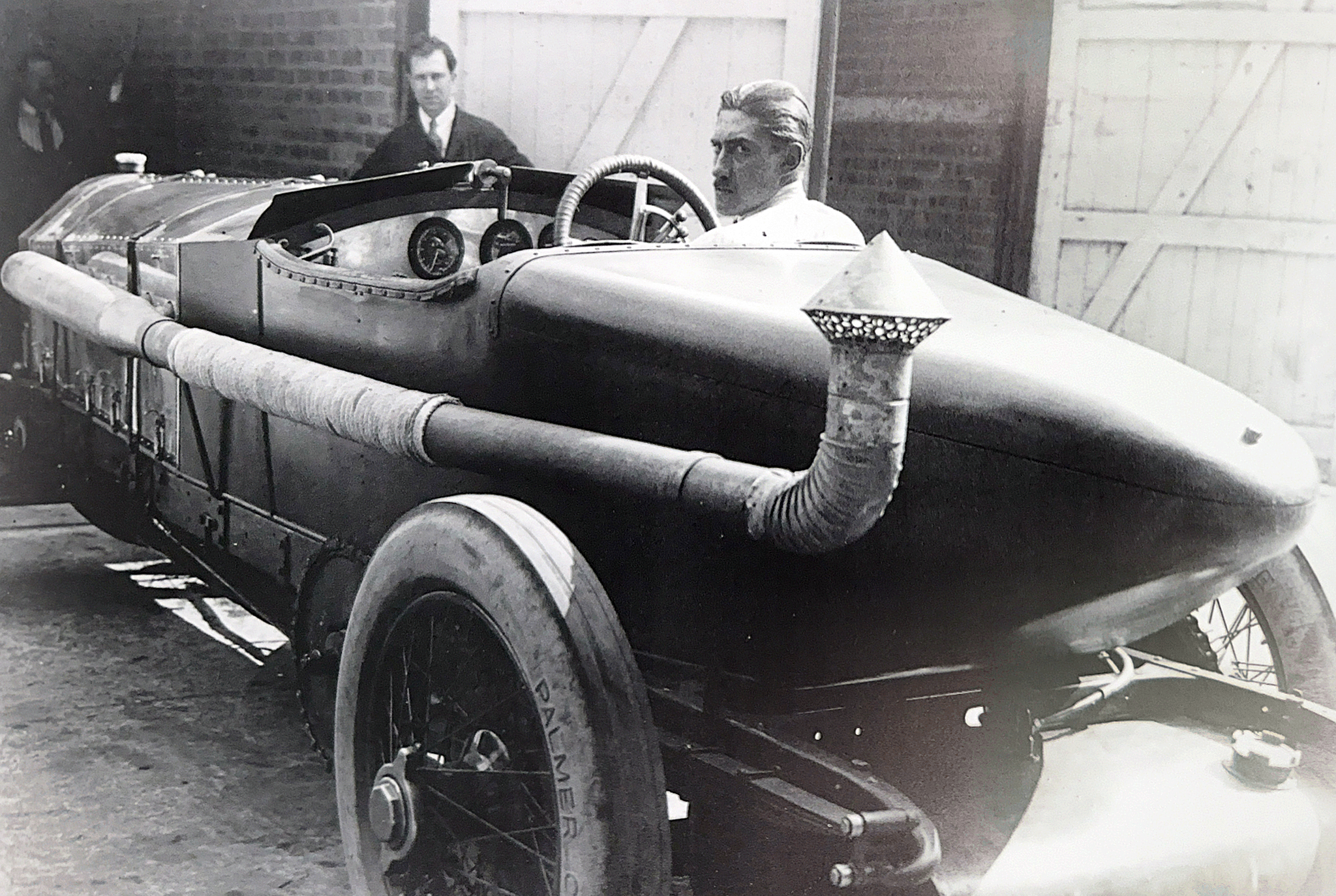

Photo: Chitty Bang Bang in it’s later 2 seater configuration

Bligh Brothers initially fitted 4 seats into Chitty Chitty Bang I 4. On its first outing at Brooklands during the Easter weekend in 1921 it won two races, and it’s unusual shape and scale made it a popular success with the crowds. It was later streamlined and modified by the coach builders into a 2-seater configuration with a more streamlined tail.

Zborowski’s presence at race meetings during the early 1920s made him a familiar sight. With each subsequent car he built, he tore down lap records at the various tracks visited across England.

Bligh Brothers ended up building bodies for all three of the Chitty vehicles; the coachwork was fabricated in Bligh’s workshops on St Radigund’s Street in Canterbury. These buildings still exist, and now form part of Kings school buildings.

Photo: Blue plaque at Bligh Brothers workshops, Canterbury. Open Plaques.

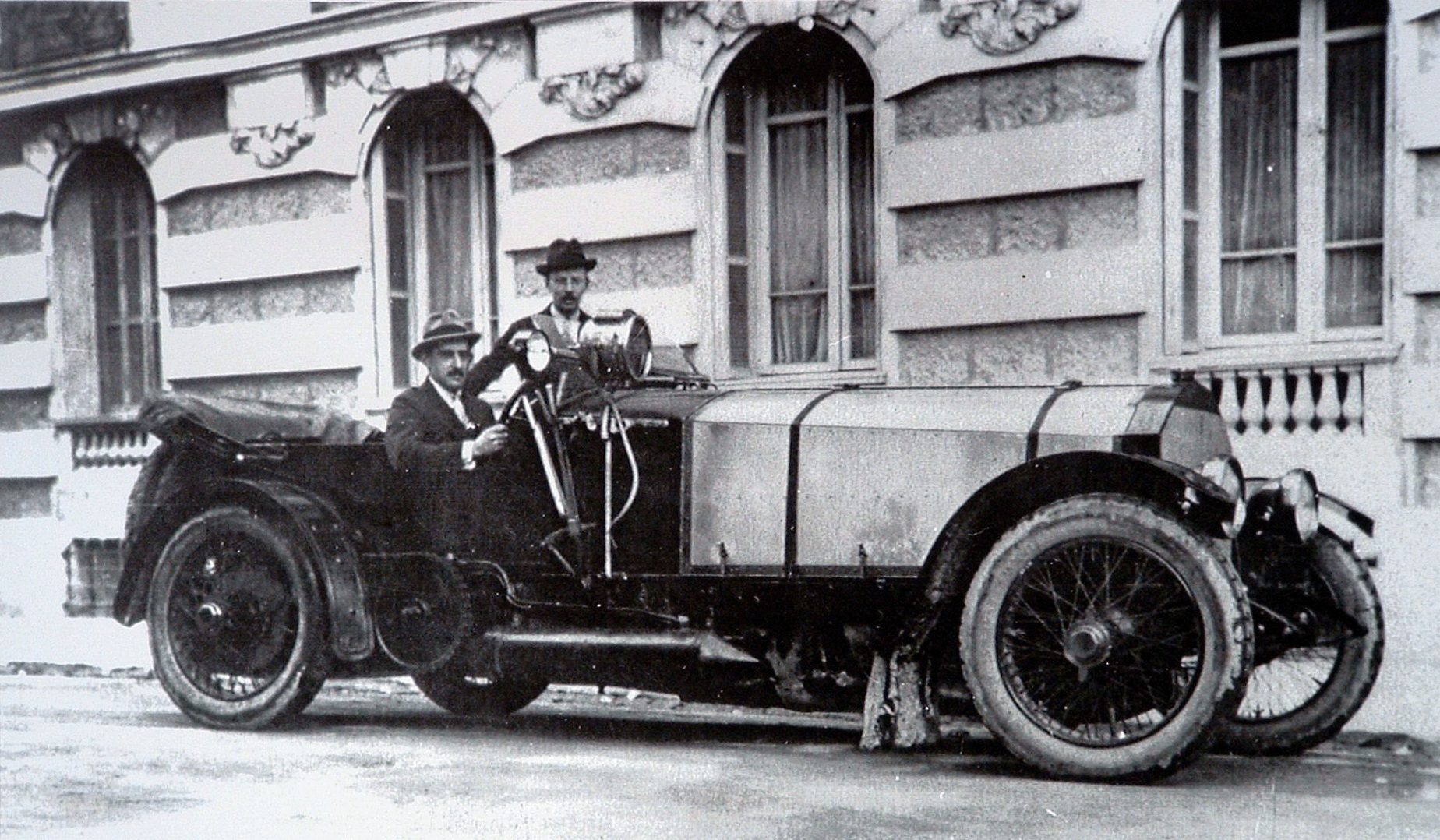

Chitty Bang Bang 2 and 3 were also successful racers, but were practical enough to use as touring cars too. Zborowski and his entourage visited the French Riviera and Morroco’s Atlas Mountains in them; a loud, glamorous but exclusively upper-class expression of 1920s motoring adventure.

Photo: Louis Zborowski and Clive Gallop with Chitty Bang Bang 2 in Nice, 1922, outside the Negresco Hotel

Photo: Chitty Bang Bang III

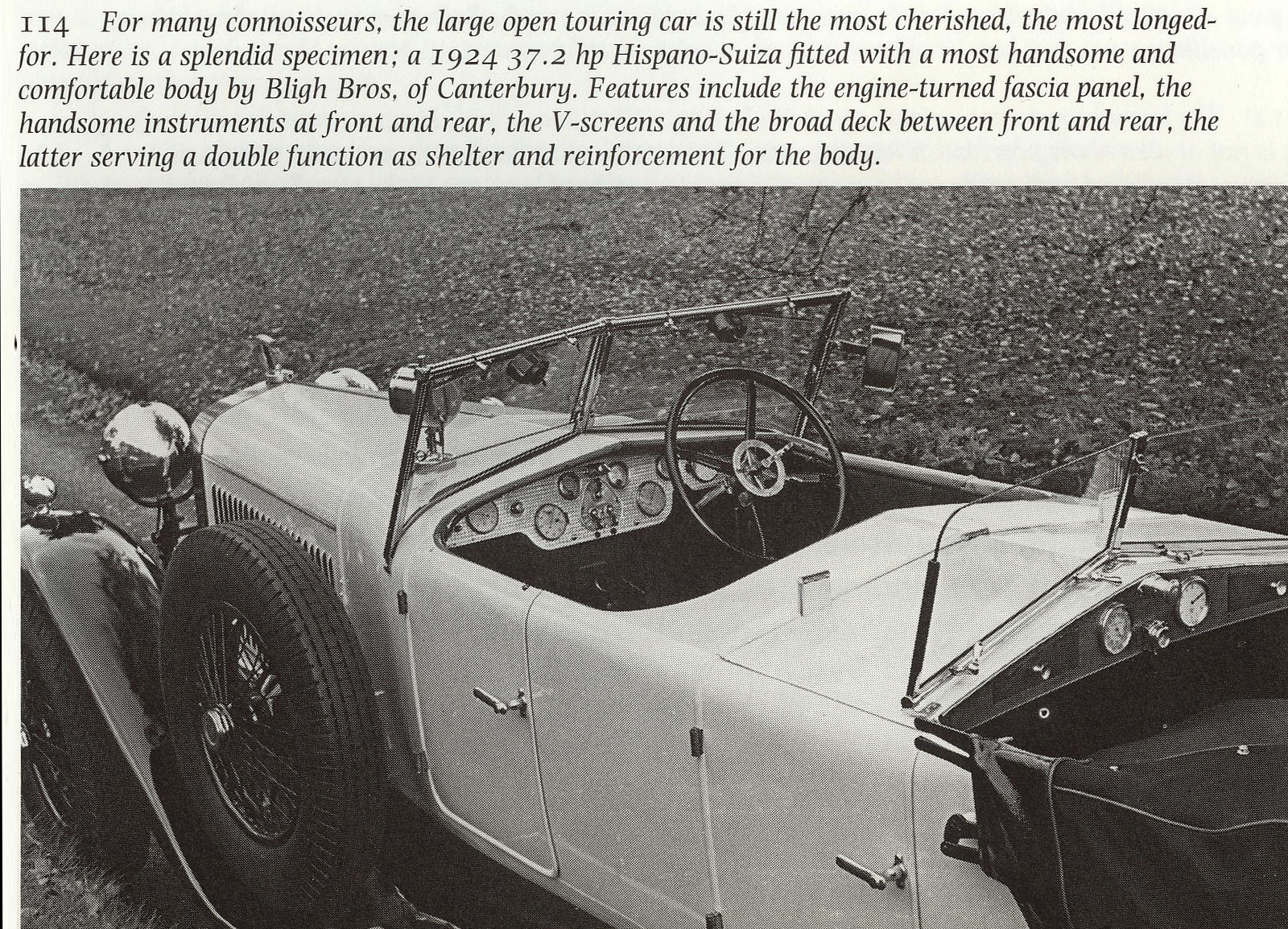

Alongside the manufacturing of his own vehicles, Louis continued to build his collection of performance and luxury vehicles, which now included an early Bugatti and a beautiful Hispano-Suiza grand tourer.

Photo: The interior of the Bligh-Brothers bodied Hispano-Suiza

Beyond the fantastical Chitty Bang Bang cars, Zborowski and his team had additional ambitions on the grand stage of world motorsport. This ambition materialised in the form of Aston Martin's entry into Grand Prix racing, marking a new era for the company.

# The first Aston Martin Grand Prix racing cars

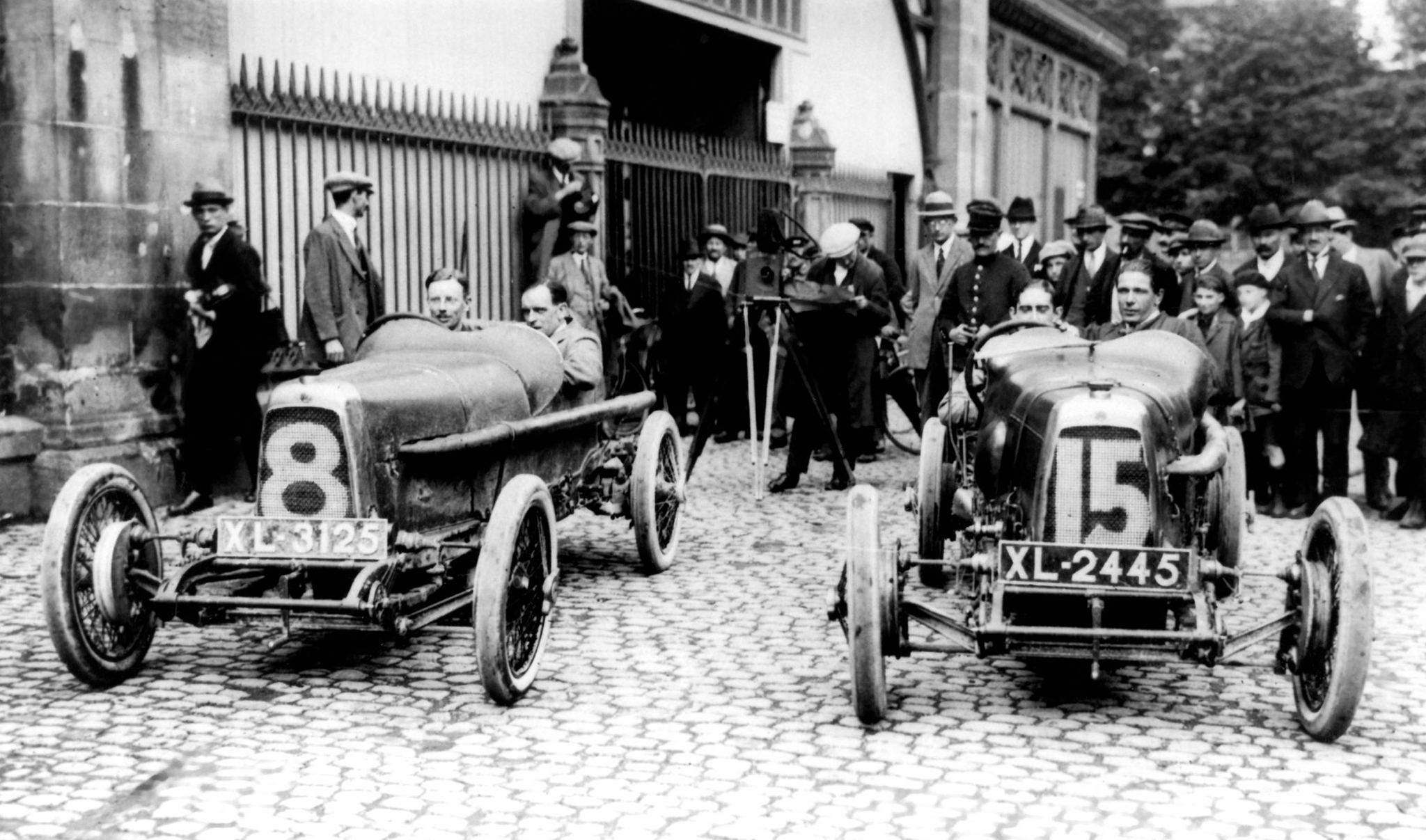

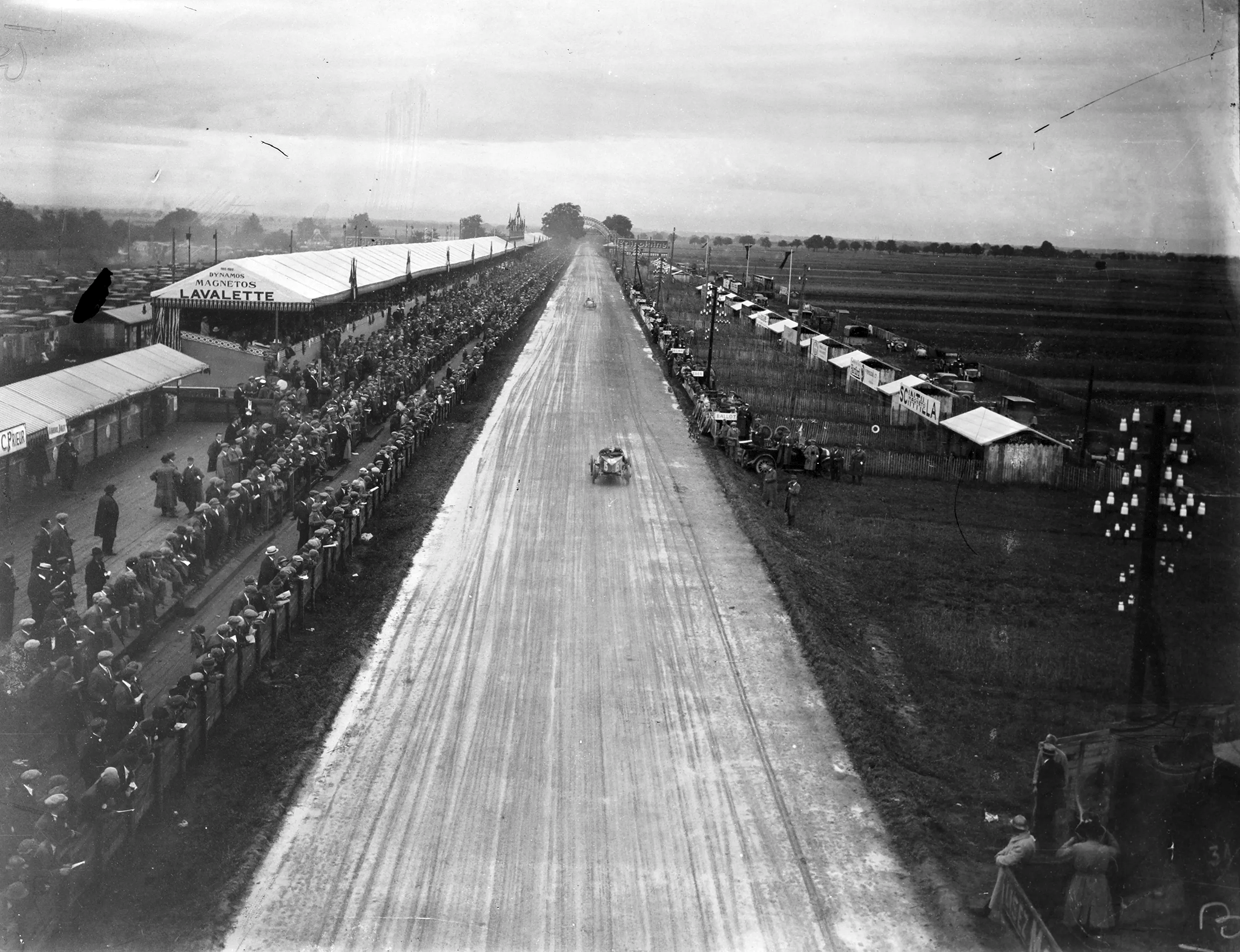

In addition to their Chitty projects, Clive Gallop and Zborowski had agreed with Aston Martin to enter a pair their 1½ litre cars in the 1922 Strasbourg Grand Prix; it would be the first time Aston Martin were to compete in a Grand Prix of any kind.

The two cars - known as TT1 and TT2 - had originally been built to race at the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy (“the TT”) , but the vehicles were not ready in time, so it was decided to debut them in France instead.

Zborowski raced in TT1 and Gallop drove TT2, the cars were liveried in two different types of British racing green. Unfortunately magneto failures on both cars resulted in retirement. Magnetos were a staple of aero-engine technology at the time, and found their way into cars too; Clive Gallop and Sidney Bligh junior (one of the grandsons of Bligh Brothers founder William Bligh) had become experts with them during WWI, both having served as part of the Royal Flying Corps.

Photo: TT2 (left) and TT1 (right) at the French Grand Prix, 1922. Hagerty

The cars were driven to race events, with regular modifications to the engine and bodywork over time. Bligh Brothers added long tail sections to them; the distinct aerodynamic tail-cone that was fitted on many of Zborowski’s racing cars became something of signature style of Bligh Brothers coach work. These tail sections were sometimes reused and moved between cars as needed.

Photo: TT2 being refuelled at Strasbourg Grand Prix, 1922. Aston Martin F1

One year after the Strasbourg Grand Prix, TT2 was badly damaged in a road accident in France while Zborowski was driving it back from the Spanish Grand Prix; Bligh Brothers undertook the repair work and the vehicle at this point required new chassis rails (these parts arrived too long and when fitted left the car with an unsettled stance).

Photo: Louis Zborowski in Aston Martin for the French GP. Zborowksi continued to develop the TT cars in the years that followed. Motorsport Images

Years later, TT2 (and associated vehicle parts) would eventually be sold to racing legend Captain George Eyston. He went on to become a three times world Land Speed Record holder in his own car (Thunderbolt), eventually achieving a record speed of 357.5mp/h.

Nothing of the Bligh bodywork from the original TT2 car appears to have survived the decades. It became the case that exterior parts were routinely swapped out by a succession of owners. However, the original engine and much of the mechanical fabric of this vehicle does remain to this day 5.

To see a working example of this legendary class of vehicle remains possible however; TT1 known as the “Green Pea” is still driven and exhibited by it's owner Neil Murray, the most complete example of Aston’s first two Grand Prix cars. To celebrate the vehicle’s centenary year, the then-recently revived Aston Martin Formula 1 team organised for former world-champion Sebastian Vettel to take Green Pea around Le Castellet circuit as part of the celebrations during the French Grand Prix weekend.

Video: Sebastian Vettel driving Aston Martin's first GP race car

# The beginning of the end

In October 1924, the 29 year old Louis Zborowski was killed, thrown from the wheel of his Mercedes when he struck a tree at Lesmo corner in the midst of the 1924 Italian Grand Prix.

Reports suggest he may have been momentarily distracted discarding a cigarette he’d just lit during the pit stop. There were reports of clutch issues and unreliable handling in the lead up to the accident, although Mercedes maintained in their official reports that this was not the case. He had been wearing the gold cufflinks his father had worn during his own fatal accident a quarter of a century before.

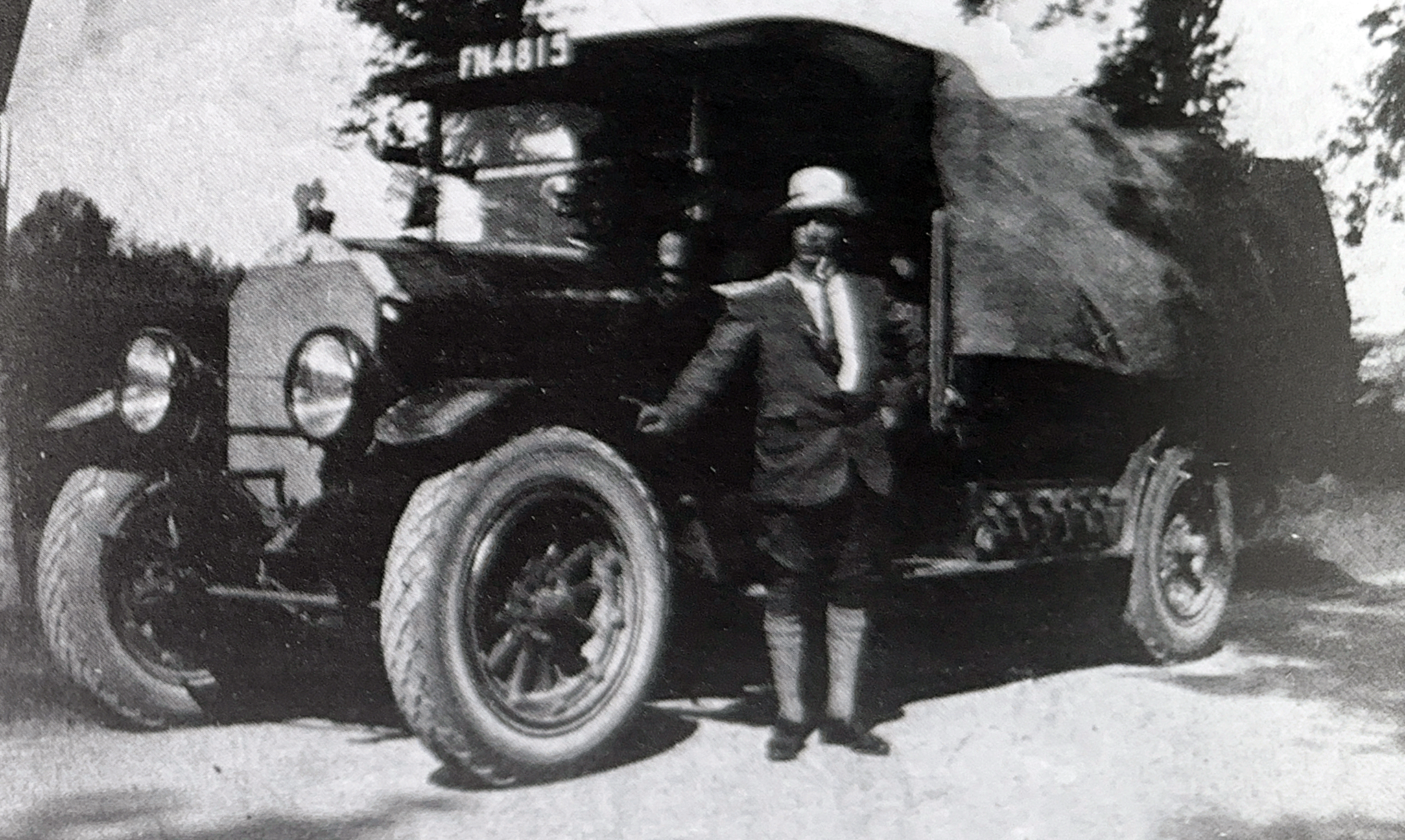

Gallop transported Zborowski’s body back to England in Bligh’s Mercedes support truck. The truck made it back most of the way, but itself expired as they approached the entrance of the Higham Park estate.

Photo: Bligh Brothers Mercedes support truck

Zborowski had made provision for two years wages to be paid to each of his staff, and Bligh Brothers were later included in the distribution of his estate. Reflecting after Louis’s death, Sidney Maslin (one of Zborowski’s mechanics) said Bligh Brothers had been responsible for manufacturing the bodies of twenty three of Zborowski's vehicles 6.

Aston Martin immediately fell into bankruptcy, and it was only in the decades after with the help of new benefactors that the firm truly found its wings and cemented it’s reputation as a road car manufacturer. It was not the first or last time the business was to face bankruptcy.

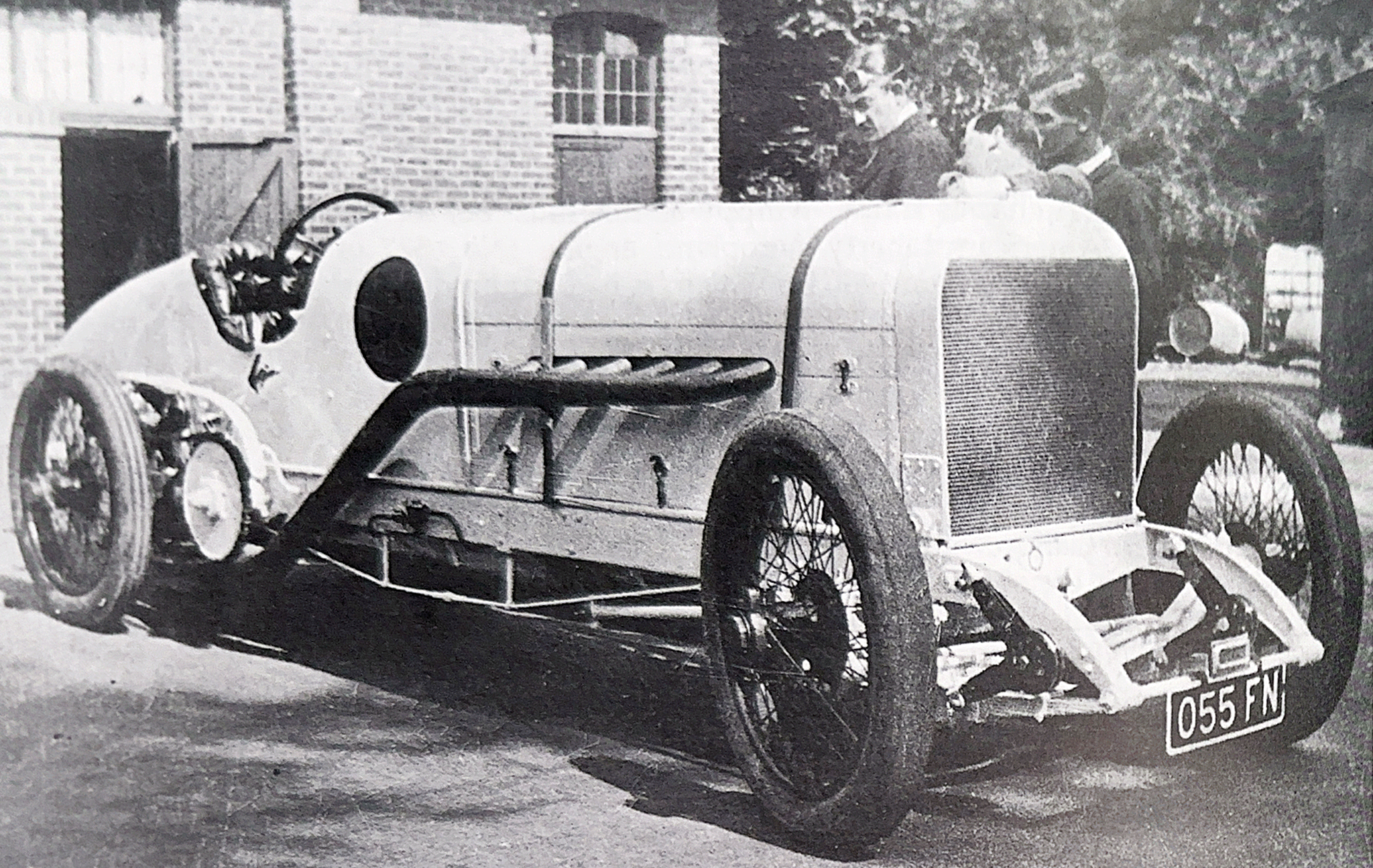

Zborowski had been part-way through developing a fourth aero-engineered car at the end of his life. A monumental 27 litre, 450 horsepower contraption known as the Higham Special (sometimes referred to as Chitty Bang Bang 4), and this was the last of his Bligh-bodied vehicles.

Photo: The Higham Special before being re-bodied as Babs

Following his death, this last vehicle was sold to another racing driver, J.G. Parry Thomas. Thomas re-bodied the car, renamed it “Babs” and reworked it to attempt to set a world Land Speed Record in 1926.

This vehicle did indeed break the record, achieving 172.09 mp/h on Pendine Sands in Wales. But during an attempt the following year to regain the record from Malcom Campbell in Blue Bird, it came to a cataclysmic end; a fatal accident which instantly killed Parry.

The remains of the car were buried on the spot where they had been wrecked on the Welsh beach. Decades later it was excavated by enthusiasts and has since been restored to working condition and is now regularly exhibited at festival events such as The Goodwood Revival.

Video: Babs (earlier Chitty Bang Bang 4) restored and on track

Records show Chitty Bang Bang 1 ended up in the hands of the sons of Sherlock Holmes author, Arthur Conan Doyle. It was abandoned and broken up for scrap. A similar ending befell Chitty Bang Bang 3.

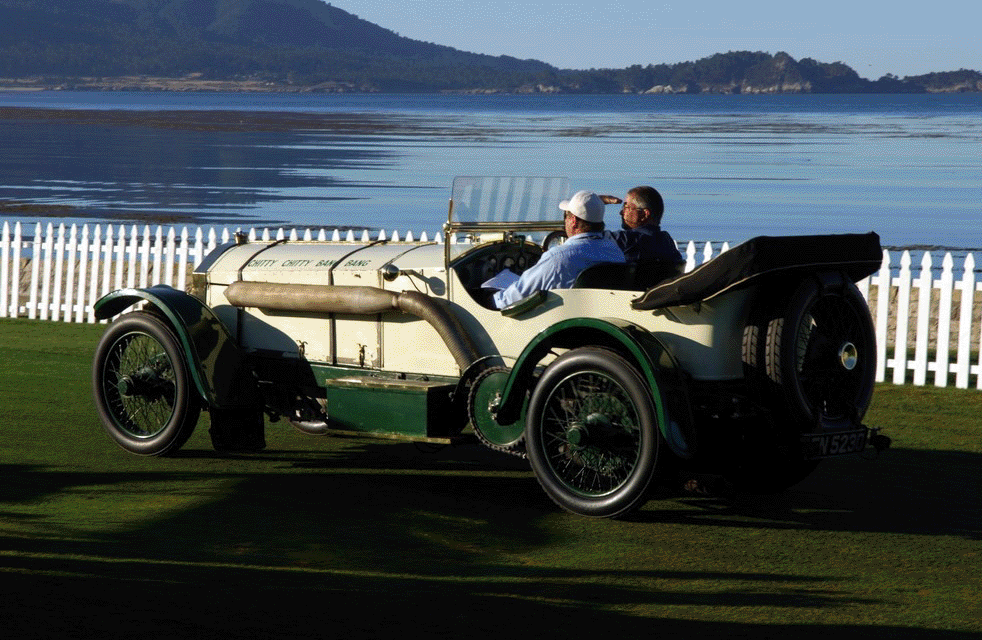

However Chitty Bang Bang 2 did survive, and remains in good working order. It is the most complete example of Bligh Brothers bodywork amongst these vehicles. The car is in private ownership in the USA. This video shows it in its present condition.

Photo: Chitty Bang Bang 2 in the modern era. Concept Carz

Another Bligh-bodied car that has survived was Louis' beautiful H6 B Dual Cowl Hispano-Suiza. Bligh Brothers customised it with a duplicate set of instrumentation for passengers in the rear seats. It is currently owned by the internationally renowned industrial designer, Marc Newson.

Photo: Designer Mark Newson with the unique H6 B Dual Cowl Hispano-Suiza. Mark Newson on Instagram

It had not only been cars though. Another transport-based project Zborowski had commissioned was the construction of a small gauge railway, built to amuse his guests at Higham Park estate. This too was built with Bligh Brothers assistance.

Sidney Bligh (a grandson of founder William Bligh) was not only a magneto expert, but also an early film enthusiast. He helped Gallop and Zborowski recreate scenes from contemporary “silent moving pictures” on the railway, and filmed the group doing so.

# The Legacies

The tales of motor innovation and racing bravado don't end with the victories on the circuit or the creation of engineering marvels. The true impact of Zborowski's life, cut tragically short, is found in the inspiration of the legacy left behind — from Grand Prix racing to fantastical flying cars.

The Chitty Bang Bang vehicles were eventually immortalised in the children’s books Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, written by James Bond author Ian Fleming.

As a twelve year old boy, Fleming watched Zborowski race the monster cars around Brooklands circuit. He also co-incidentally made a series of visits to the Higham Park estate, which after Zborowski’s death came into ownership of one of Fleming’s relatives. These encounters inspired Fleming to write the books, which were later adapted into the film by Roald Dahl. The cars featured in the film are a fantastical re-imagining of the Chitty cars (and are not Zborowski’s original vehicles).

Zborowski’s friend and engineer, Clive Gallop continued his career in the growing luxury automotive industry, and made a name for himself as engineer to the Bentley Boys. He became instrumental in developing the most iconic of their pre-war vehicles, the 4 1/2 litre Blower Bentley.

Photo: Clive Gallop's work, the Bentley Blower

Fleming’s contribution to our modern familiarity with every one of these vehicles can’t be understated; somehow he played an instrumental part in how each car has been elevated to iconic status.

After all, it is not Aston Martin, but one of Gallop’s 4½ litre Blower Bentleys which James Bond drives in the original books.

Later film adaptations of Bond helped Aston Martin’s sports cars including the DB5 and DBS earn their own iconic status, an association which has now endured for over half a century.

Chitty Bang Bang became a timeless byword for magical flying cars through his fantastical stories for children.

Zborowski’s Higham Park railway was eventually broken-up and sold, and today operates as the Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch railway. The locomotive was renamed Count Louis in his memory.

Bligh Brothers continued to trade in Canterbury for many years after Zborowski’s death, but slowly moved away from coach building. The last of the Blighs departed the company in the decades that followed, and it operated as a motor garage for its final years. The business eventually folded in 1973.

My own direct line of ancestry connects me to Bligh Brothers through William Bligh’s sixth son, James, who went on to establish his own coach-building firm in Ramsgate.

James Bligh’s grandson (my own great-grandfather) Harry Bligh was bought-up in the family trade. Sometime in 1923-24, while his cousins in Kent worked on Chitty Bang Bang, his coach building expertise was sought out by Sir Herbert Austin to manage the body shop, where he oversaw coachwork for the seminal Austin 7, which popularised mass-motoring in the UK. The majority the male descendants of the Bligh family found themselves operating in the industry.

A century on, coachbuilding has all but passed into the history books except at the very highest-end of bespoke automotive production. In the modern era, of those brands which still do coach-build (albeit in an extremely limited numbers) Aston Martin and Bentley remain as two firms in the small minority that do continue the tradition.

Despite the short years of Louis Zborowski’s life, he became a powerful catalyst in the development of British motor-racing. He was the first to save Aston Martin from bankruptcy and served as a white knight to the struggling Bligh Brothers of Canterbury. His life and cars served as a direct inspiration to Ian Fleming’s most well known literature and films, and he directly and indirectly assisted in successful land speed records even after his death – on reflection a remarkable legacy for someone who died at only 29 years old, a century ago this year in October 1924.

# Thanks

Thank you to Stephanie Higgs for all her research assistance. More of her own writing on Bligh Brothers can be found on her blog. She spent hours fact-checking the history, and improving my writing!

Also thank you to Steve Waddingham, Aston Martin's in-house historian and archivist who has been a great help in shining light into the (often messy!) history of the cars.

# Notes

Note 1: Bligh Brothers petitioned for bankruptcy in 1913 (existing then as an unincorporated partnership) (Bankruptcy notice - 15th February 1913, Whitstable Times, Sale of business items - 29th March 1913, Whitstable Times). They did so again in the summer of July 1916 as conscription started to reduce their workforce. Details of exactly when the full Bligh Brothers ownership by Zborowski commenced are unclear, but we can reference when he became signatory on the leases for their workshops - see Note 3.

Note 2: Established between 1825 and 1828 according to court records related to the later bankruptcies.

Note 3: Ownership of Bligh Brothers by Zborowski The Racing Zborowskis, page 84 & 85.

Note 4: Source The Racing Zborowskis, page 74 & 76.

Note 5: The very earliest racing Aston Martins have survived to this day, but frenetic workshop activity over the last century means it’s often unclear which parts started out on what car. Tracing the provenience of early Aston Martins is a complex, and Steve Waddingham has been an excellent source of information and fact-checking throughout the process of writing this.

Note 6: Source The Racing Zborowskis.

This post was first published on Sun Mar 03 2024