Turner, Newhall Hill & The Jewellery Quarter: A Historical Mystery

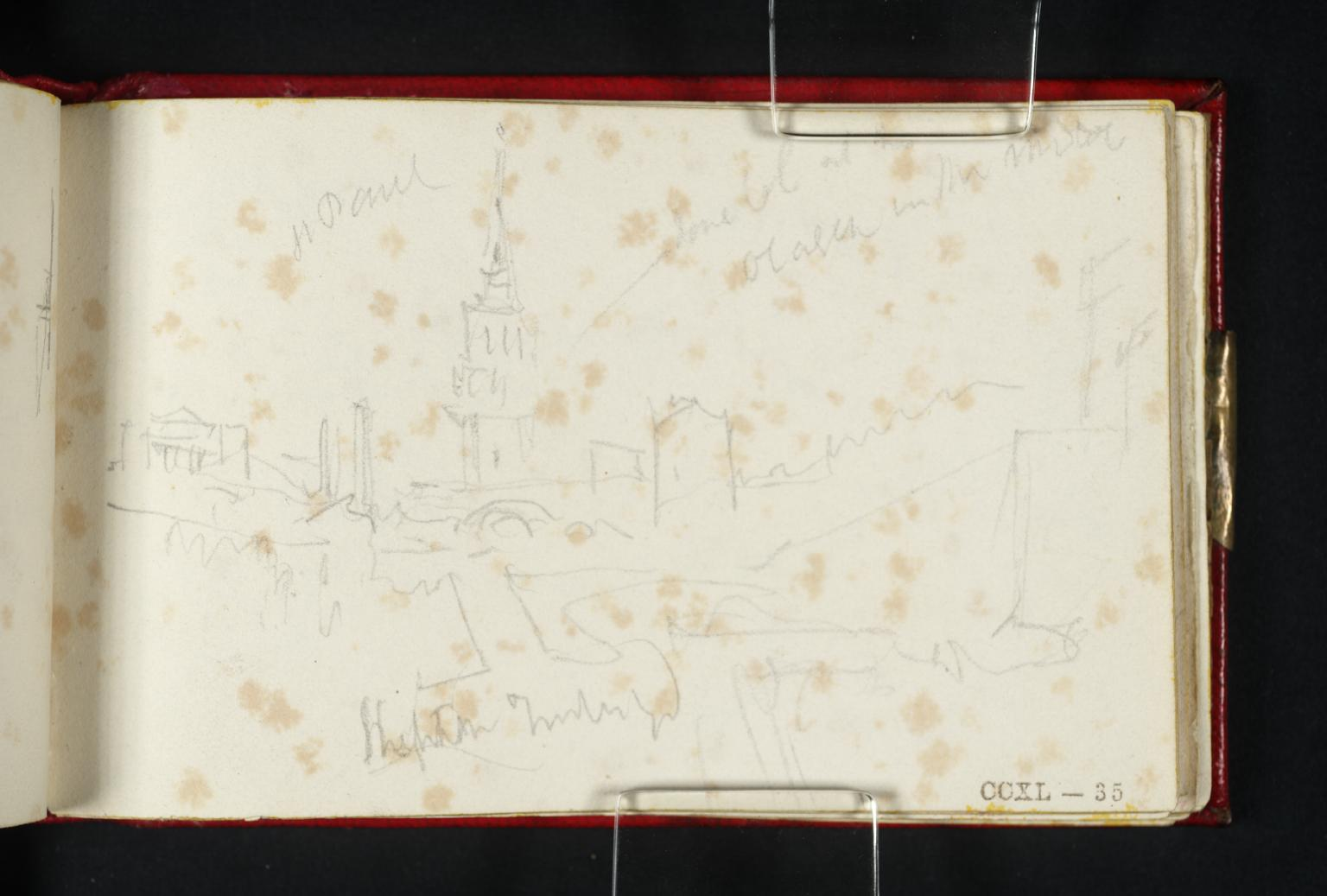

I recently discovered that in the archives of the Tate lies an intriguing pencil sketch from 1830, depicting Birmingham's St Paul's Church and its surroundings. The artist? JMW Turner.

Whilst indexed in the Tate's sketchbooks over a decade ago, this piece of Birmingham's artistic heritage remained largely unnoticed until recently, and provides a window into a pivotal moment in the Jewellery Quarter’s history.

The original sketch of St Paul’s church by Turner, 1830 (Tate Archives)

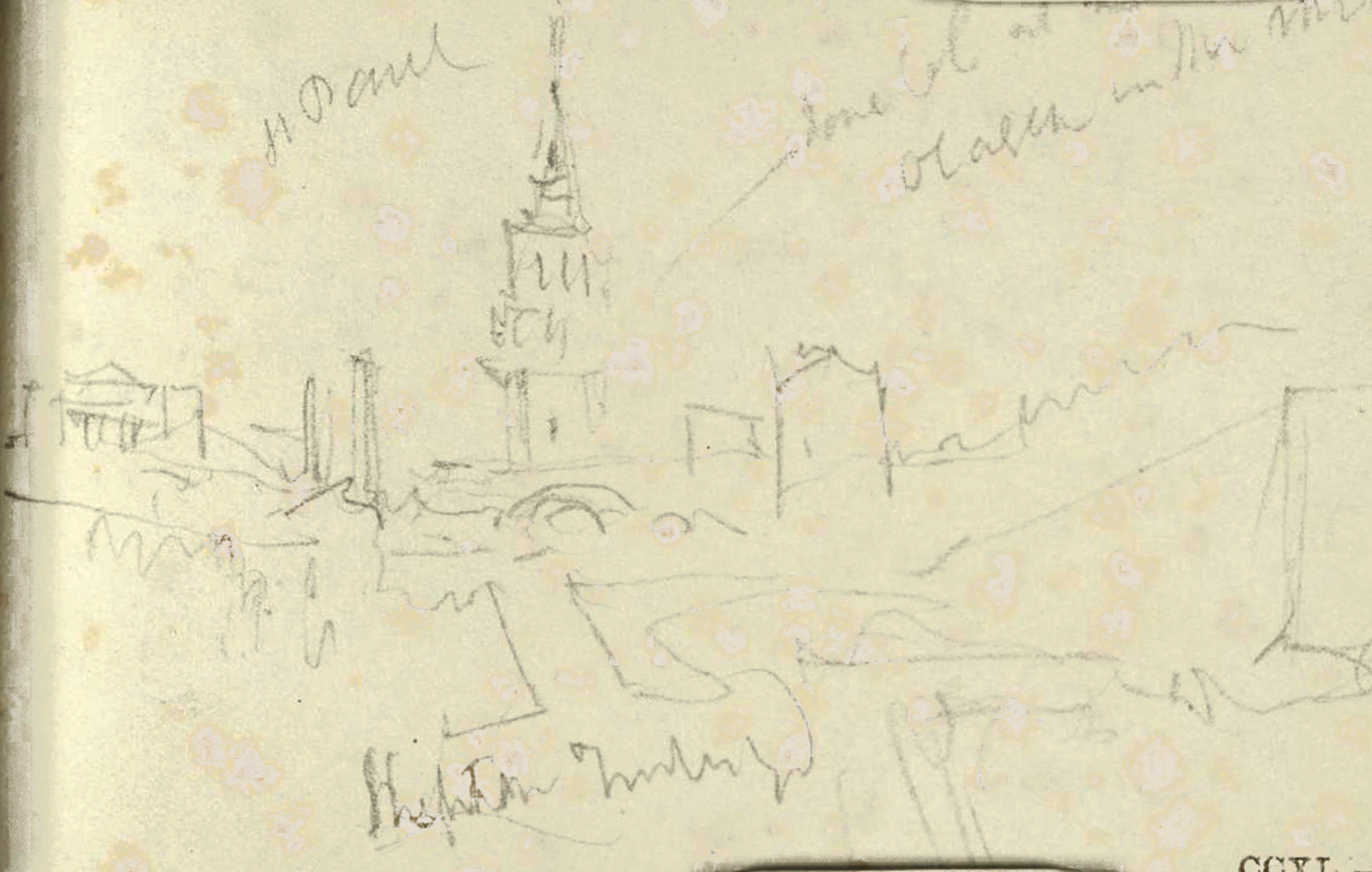

An enhanced version of the same sketch.

The sketch, though faded, contains valuable details of the landscape. Art critic John Ruskin, who once possessed the notebooks, added his own annotations in red pencil. The words "St Paul" are visible to the left of the church spire, providing immediate confirmation of the subject. However, the exact location from which Turner made his sketch presents an intriguing mystery.

St Paul’s church today, from the upper side of the square.

# A Complex Perspective

Today, St Paul's church stands surrounded by some of the last remaining Georgian residences in Birmingham's city centre. Prior to Turner’s visit it was familiar to notable figures including steam engine pioneers Matthew Boulton and James Watt (who rented pews there), then later Washington Irving. The American author wrote his most notable works "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle" whilst lodging with his sister’s family, a stone’s throw from the church.

The steeple, a prominent feature in Turner's sketch, was a relatively recent addition when he drew it, having been completed around 1822 (the church itself dates to 1777).

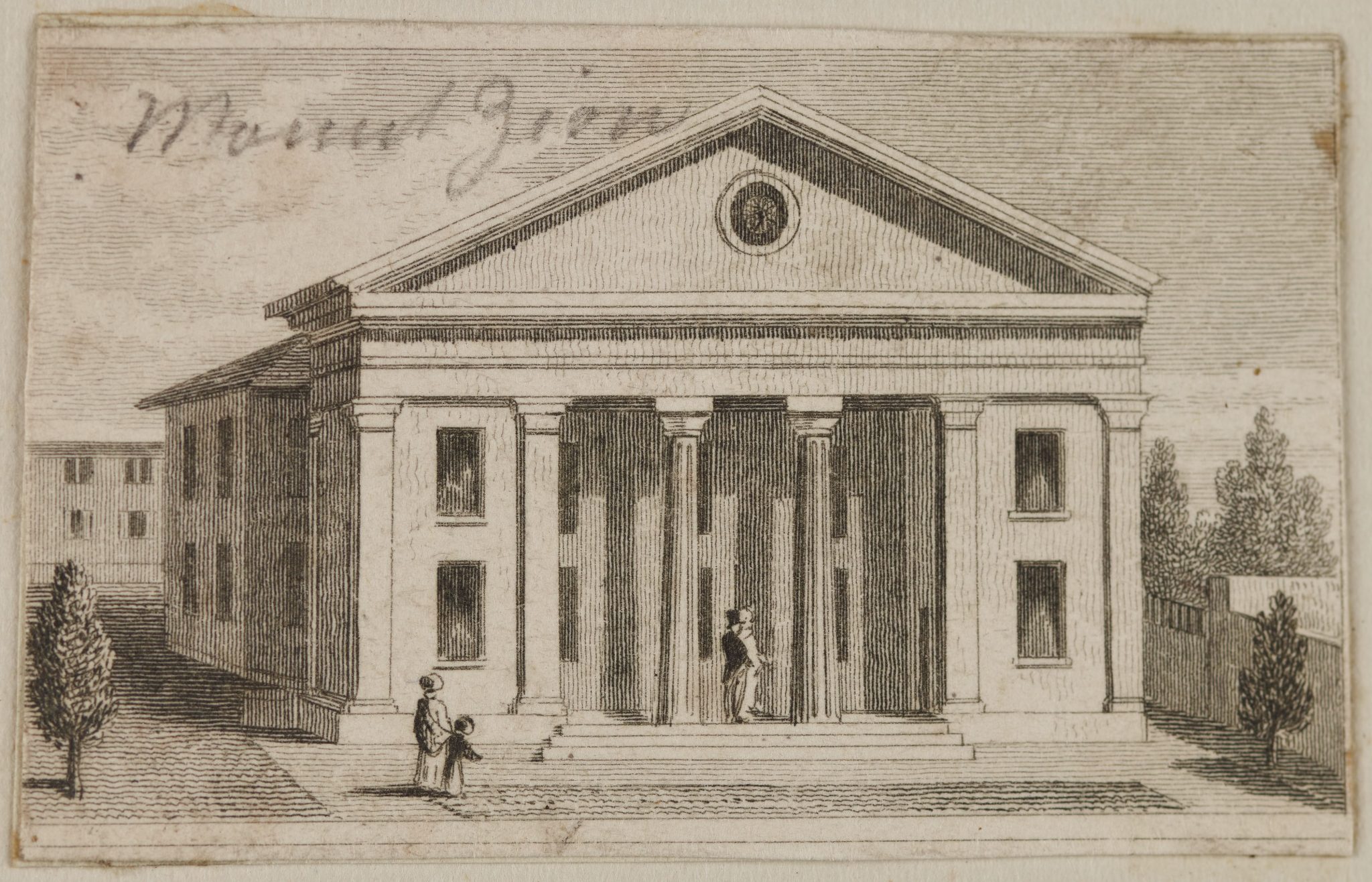

The distinct column-fronted building to the left of St Paul’s church is almost certainly the Mount Zion Baptist Chapel, which stood on Graham Street from 1824 to 1913 (now the site of Sovereign Court). While the buildings appear close together in the sketch, they were actually about 250 meters apart - a perspective that raises interesting questions about Turner's vantage point.

A sketch of the facade of the Mount Zion Baptist Chapel (briefly known as St Andrews Presbyterian Chapel when it was first constructed) facing Graham Street.

A photo of the same building towards the end of its existence.

# The Geography of Industry

The landscape Turner encountered was dramatically different from what is visible today; the density of buildings was much lower, and this area formed the outer edges of the emerging urban sprawl, the fringes of a mixed residential-industrial area.

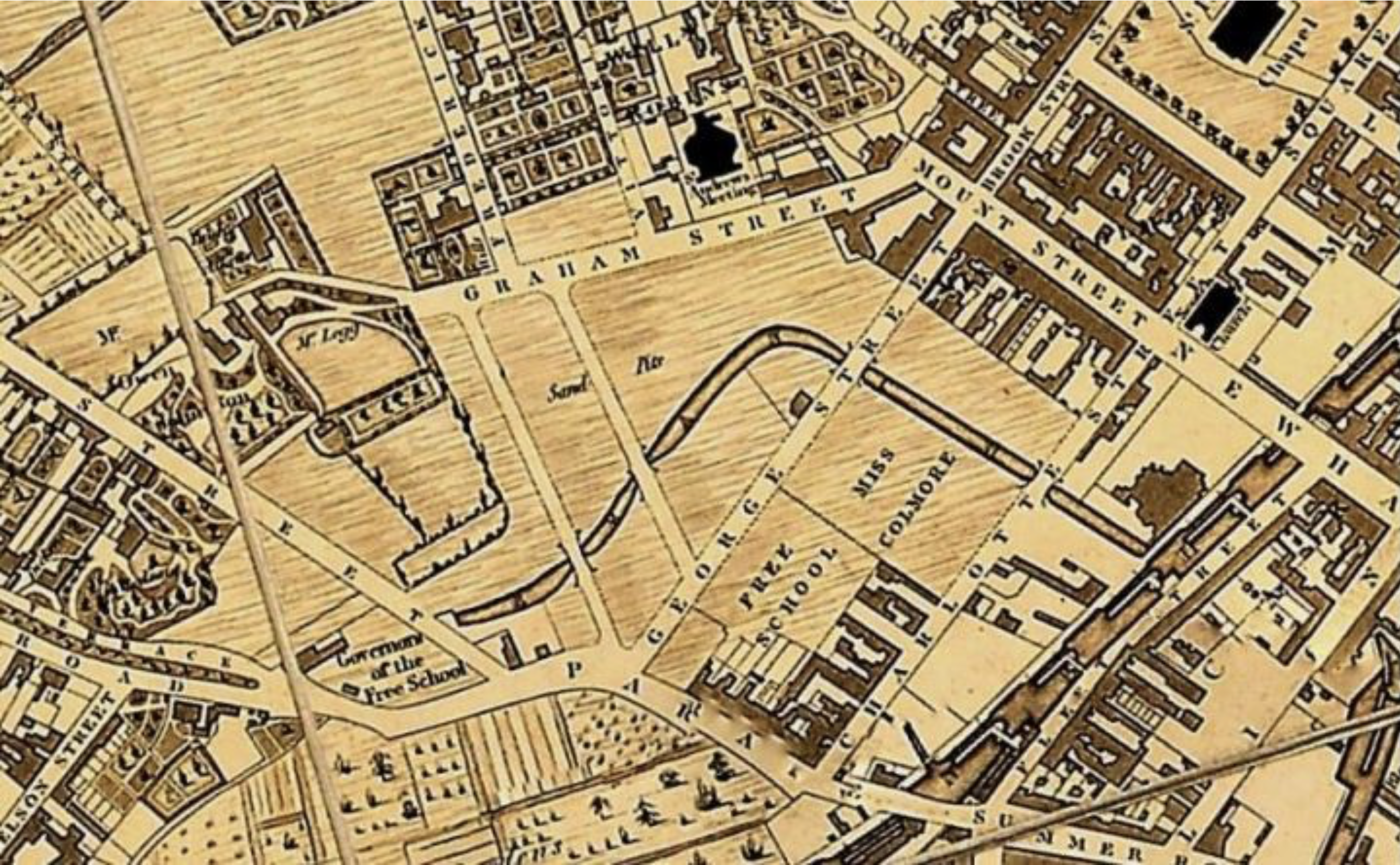

Between Graham Street and George Street lay a large sandpit that had serviced the town's brick-making industry. Mount Zion Chapel stood on a high promontory overlooking this industrial excavation on Graham Street, which followed the top boundary of the pit and George Street marking its lower edge. The remaining edge of the pit formed a distinctive triangular wedge of (removed) land known as the New Hall Hill (and sometimes as Camden Hill, a name that also lives on today in modern street names; Camden Street, Camden Drive and Camden Grove). The modern derivative “Newhall Hill” is the roadway that connects George Street and Graham Street - but at the time this was not laid out.

(Confusingly, the “New Hall” building from where the name originally derives, was located on similarly named Newhall Street, between Great Charles Street and Lionel Street).

The residential red brick buildings in the mid-ground lie a number of metres below the ones immediately behind. They are constructed inside along the edges of the old triangular sandpit, bounded by modern Newhall Hill to the left, Graham Street to the right and George Street running horizontally across the photo.

# The Mystery of the Canal and Bridges

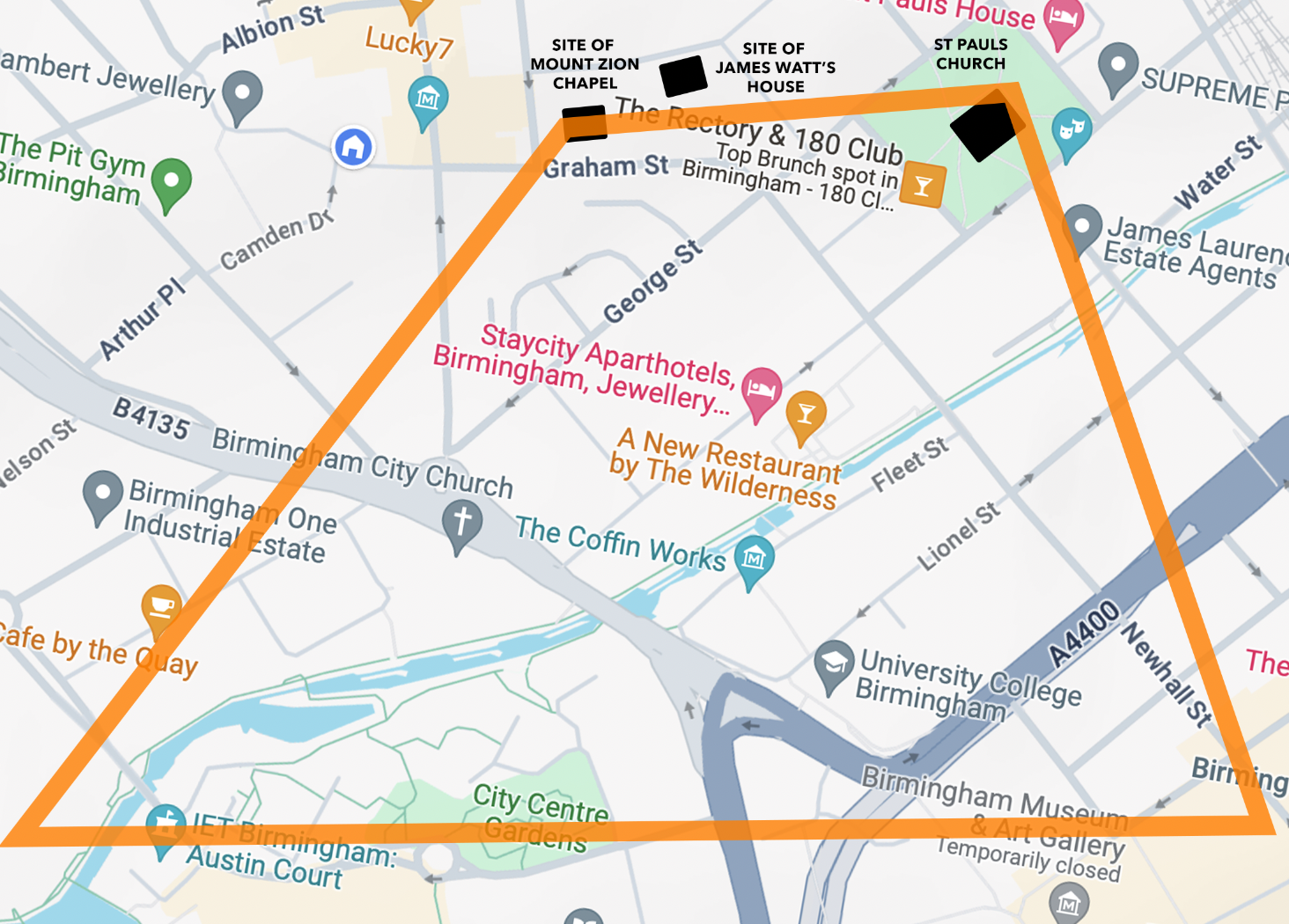

One of the most puzzling aspects of Turner's sketch is the bridge crossing what appears to be water in the mid-ground. Logically the perspective of the site seems to align with him being stood in the sandpit looking at St Paul’s, towards the bridge, but practically it doesn’t quite work.

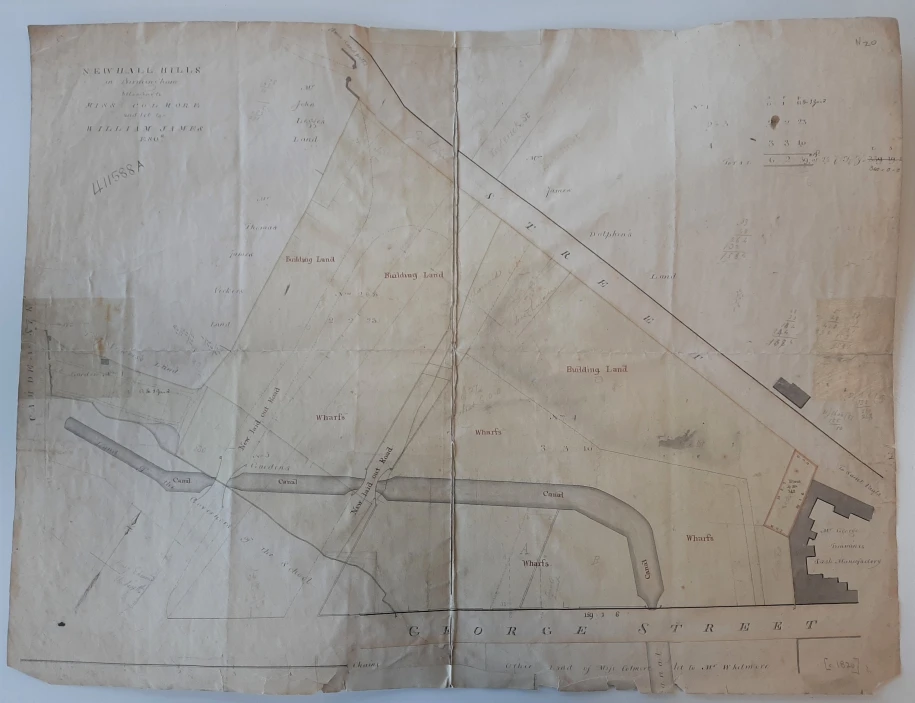

The Whitmore Arm canal, which once ran from Newhall Street basin parallel to Newhall Street, then curved along the flat sand behind George Street, would seem a likely candidate for being the waterway. This canal branch, built to transport sand, was part of an ill-fated and short-lived enterprise by William James. It was intended to allow easy transport of the sand to the central canal lines. But much like other canal basins nearby, these branches were infilled at a later date, and there is little trace of them today. Sometimes it was because the constructors were surprised to discover the local sandy earth was more permeable to water than perhaps they had anticipated! However, at least in the case of Whitmore's Arm, the canal remained for a long time, and remained partially "in water" until the mid-20th century when it almost completely disappeared as a consequence of new development.

Maps from c1820 and 1824 show the route of the freshly dug dog-legged canal, with bridges inside the bounds of the sandpit. This ought to help with orienting the sketch, however the historical evidence presents some additional challenges.

The c1820 map of the sandpit, showing the Whitmore Arm canal, bounded by George St (bottom) & Graham St (top).

The 1824 map, dedicated to the Earl of Dartmouth by the publishers, shows a wider view of the same area, with St Paul’s appearing in the top-right, and Mount Zion Chapel in top-centre (labelled here as St Andrew’s Meeting, as it was known for a short period of time).

However, when you try to align Turner's perspective with these historical features, no single location seems to provide the view depicted in the sketch. The bridge's alignment with the church spire, the curve of the canal, and the relative positions of the buildings resist a definitive placement of Turner's vantage point.

I remained determined to find an answer, and attempted to resolve this with the help of local historian John Townley who is intimately familiar with the local maps and estates. He reviewed the sketch too, and re-consulted the contemporary source material, but proposes that the two "laid out" roads crossing the canal in the map were more-likely-than-not never built due to the adverse gradient of the pit site.

The mapmakers seem to have been actively seeking out information on partially complete and planned building works, to try and ensure the published result would be be as up-to-date as possible. However, the consequence of this 'proactive' decision bears out when comparing the various maps now, each of which provides a slightly different idea of the street layout; and which makes it very hard to determine what the reality was!

What John’s exploration did yield however was identification of local business “Houghton Timber Y[ar]d” - picked out of the sketch in Turner's annotations. Records show this business was located at 18/19 Charlotte Street alongside part of the Whitmore Arm. This information is not available from the Tate Gallery’s own interpretation. Looking into the background, and considering the orientation, he suggests that “the two … chimneys between St Paul's & Mount Zion could be George Brindley's Rolling Mill on the south side of Northwood Street between James Street & Caroline Street, or more probably Richard Southall's Mount Street Steam Mill.” Although not quite the level of precision I was hoping for, this does at least appear to validate that the sketch was drawn from this general prospect.

# A Landscape of Reform

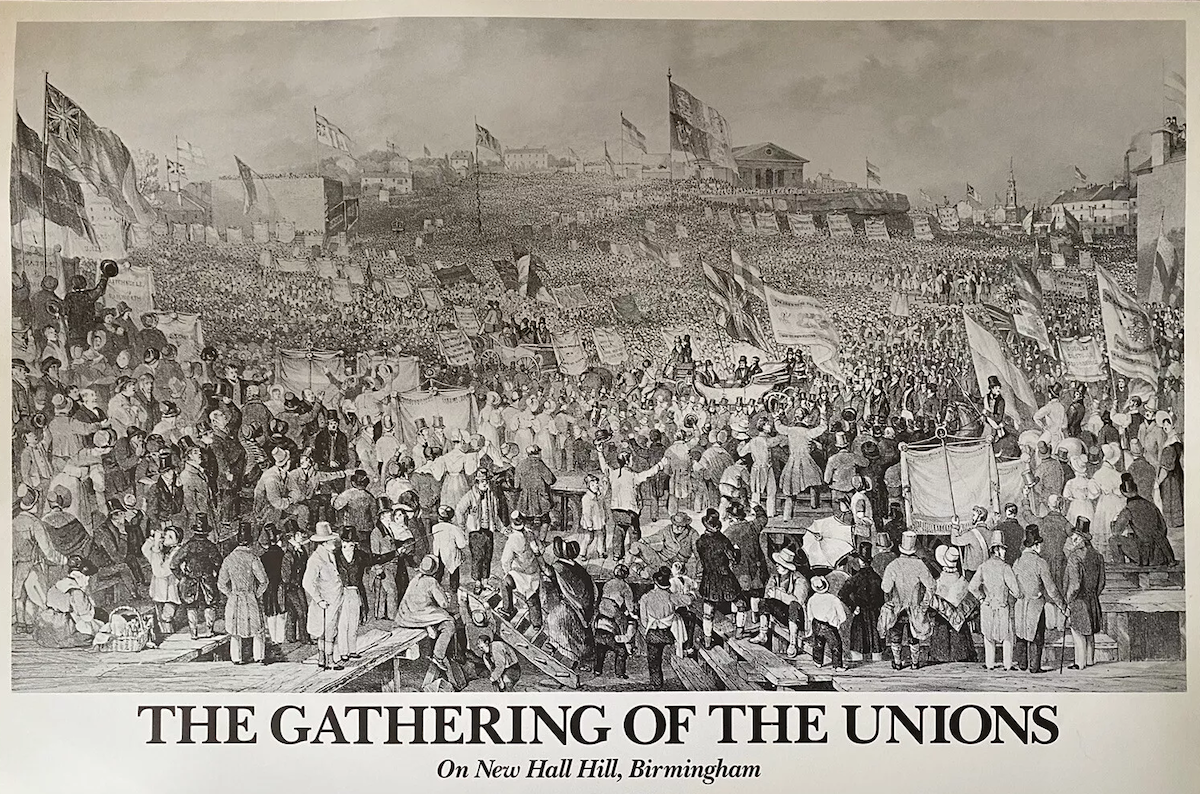

The area captured in Turner's sketch would become the site of significant historical events soon after. In May 1832, just two years later, the reformer Thomas Attwood of the Birmingham Political Union stood at New Hall Hill before huge crowds to advocate for the improvement of voting rights and expansion of the franchise. The earthworks became a popular location for political gatherings after the sand-extraction stopped in 1817, and this particular group was concentrated on reform of the ancient parliamentary structures which failed to capture Birmingham's explosive population growth, and kept the town extremely under-represented in Westminster.

The Reform Act passed and received royal assent just days later, putting Attwood into the House of Commons as one of Birmingham's first two MPs. Others who delivered orations here included the renowned Irish reformer and MP Daniel O'Connell, who also championed reformist causes.

The Meeting Of The Unions On Newhall Hill, Birmingham, 16th May 1832, by Benjamin Robert Haydon

Several paintings, etchings, and drawings of these momentous gatherings survive and give us further perspectives that might give clues. Whilst we must treat any drawn matter with careful consideration (and room for artistic licence), they offer valuable insights when viewed collectively.

The view north, from the bottom of modern Newhall Hill up towards Mount Zion Chapel, with St Paul’s visible on the right. A strong likeness to the view Turner sketched.

A second engraving of the same scene of the meeting of the Birmingham Political Union, this time facing west. New Hall Hill rises in the middle of the page. Zion Chapel would be to our right, and St Paul’s behind us. It confirms a consistent topology as the first engraving (the central freestanding flag pole, word “Order”, and buildings can be used to anchor the orientation).

These two etchings, reportedly drawn on the same day as the events in the sandpit, show the scene from different angles - one facing north, the other west. The north-facing perspective bears striking similarities to Turner's view of the landscape, showing Mount Zion chapel on its promontory, the banking of the sandpit beneath it, and St Paul's spire on the far right. The western view confirms the consistent topology, with Newhall Hill rising from south to north across the middle of the page.

As an interesting continuation of the story of social reform, Mount Zion chapel would, a number of decades later, become the ministry of another Birmingham champion of reform, civic gospel preacher George Dawson.

# Industrial Transformation

The transformation of this small triangular patch in the early Jewellery Quarter reveals much about Birmingham's rapid industrialisation.

Part of local industrialist James Watt's marketing genius was to devise the unit - horsepower - which helped his customers instantly calculate exactly how many animals (with their associated costs, space, and upkeep) could be replaced by just one of his steam engines. From 1777 - coincidentally the same year the building of St Paul’s commenced - Watt lived in a house on Harper's Hill, in the space between St Paul's church and Mount Zion chapel. He was there for 13 years.

By the time Turner sketched the scene, Birmingham was employing about 2,000 steam horsepower (hp). Forty years after that, the local usage of steam power had ballooned to an astounding 180,000 hp.

A photo showing the recently excavated remains of James Watt’s house (1777-1790). From this orientation, St Paul’s church spire is visible in the centre. The location of the sandpit and Mount Zion chapel is not visible, out of shot to the right. Photo kindly by permission of George Demidowicz, advisor to the archeology project at Harper’s Hill.

Washington Irving captured the exact character of the area in 1815: “Every thing around me too, is so exactly to my taste. The House, the grounds, the Household establishment, the mode of living; never before did I find myself more completely at home.” (July 5th, Letter from Washington Irving to his friend Henry Breevort in the USA).

Between Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo in the same year, and the passing of the Reform Act in 1832, this vista transformed from a semi-pastoral retreat at the edge of the town dotted with large houses, to a dense concentration of hybrid industrial-residential workshops. Modern Newhall Hill became a formalised thoroughfare in May 1833, catalysing the urbanisation of the immediate area (but also marked the moment when the political gatherings moved away from the site).

The pace of change accelerated rapidly. Within 10 years, Joseph Gillot's expansive and world-leading Victoria Works pen manufactory appeared on Graham Street (built 1839, it still stands). By this point the surrounding streets were packed out with dozens more tiny factories operating in a mass of former and active residential buildings. The mix occasionally led to tragic consequences and in 1862, immediately opposite Mount Zion Chapel, a huge (but not rare) explosion in a percussion cap manufactory killed 9 and injured 30 more.

The site of the 1862 percussion cap factory explosion, 60-70 Graham Street.

The buildings in the foreground occupy the sandpit, and later site of the fatal explosion on Graham Street, as viewed from the Harper’s Hill excavations today. Credit: George Demidowicz.

# Turner's Presence

Like the exact location of where he made the sketch, exactly why Turner happened to be in this specific part of Birmingham remains unresolved.

The Tate's notes accompanying this sketchbook suggest he was touring the English midlands in search of material for new watercolours, and the sketch appears alongside several other unidentifiable Birmingham scenes. At 50 years old, he may have used the trip to visit some of the interesting figures that lived here, though without supporting diary evidence, this remains speculation. I haven’t found any evidence that this sketch was ever worked up into a final artwork, and perhaps there was an element of artistic licence or recalling the scene from memory that means we just won’t ever be certain where he was standing when he sketched it.

All we can conclude - the orange box marks the plausible area in which Turner seems to have been standing in order to see both buildings with a viable perspective.

# Modern Echo

Today, this corner of the Jewellery Quarter has returned to a primarily residential character. All that remains of the Whitmore Arm canal is a bridge and the "stub" of a wharf near Newhall Street, where it once joined the main Birmingham & Fazeley canal in the middle of the still-existing Farmer's Bridge flight of locks.

The stub remains of the Whitmore Arm canal, February 2025.

While we may never pinpoint exactly where Turner stood to make his sketch or discover who he might have been visiting, his sketch preserved a crucial and short-lived moment in Birmingham's urban transformation. The drawing captures a landscape on the cusp of sweeping change, many decades before the town would be granted city status and transform into the industrial powerhouse it would later become.

For more detailed information about the development of the area immediately around Newhall Hill, I recommend John Townley's research, including this piece on the Whitmore Arm, local maps and the Colmore estate. Thank you to George Demidowicz for the gracious use of his photos from Harper's Hill.

This is dedicated to DPJ, whose passion for exploring the past helped shape my own.

This post was first published on Sat Mar 08 2025